Reassessing the impact of climate change on evolution

A new study co-authored by an HKBU researcher has cast doubt on a longstanding hypothesis that climate variability acted as a major driver of evolution in mammals, including our human ancestors.

Published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study combined climate data with fossil records of large mammals that lived in Africa during the past four million years, and it has revealed that times of erratic climate change are not followed by substantial upheavals in evolution, as proposed by the popular variability selection hypothesis.

Significant study

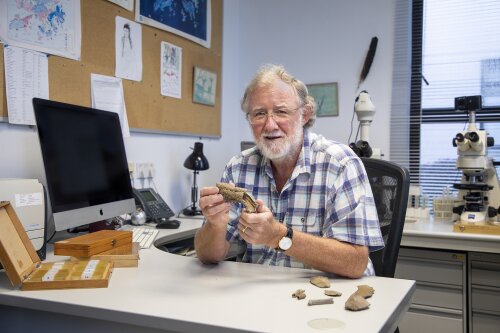

“We have proven for the first time that there is no link between climate change and mammalian evolution at longer time scales, and by inference, human evolution,” says Professor Bernhart Owen, a Research Professor in the Department of Geography and a co-author of the paper. “While evolution reflects the survival of mutations that best fit an environment, it may be that ecological drivers are more important than climatic drivers.”

To reach this ground-breaking conclusion, the researchers had to solve two issues. First, to further explore the link between climate change and evolution, they had to create a composite history of shifts in the African climate. Second, they also needed to calculate the rate at which new species arise and become extinct.

In terms of the climate data, when the researchers looked at environmental samples, they found that variability during the Plio-Pleistocene, a period of the Earth’s history that spans roughly the last five million years, mirrors changes in the Earth’s orbit and orientation with respect to the sun. In addition, the researchers observed a long-term trend of increasing environmental variability across Africa attributable to variations in global ice volume and ocean temperature.

At the same time, the researchers also looked at the fossil record of large mammals such as bovids, a family that includes antelopes and other large herbivores, as according to Professor Owen, there are just not enough human fossils to do anything statistically useful. The team then used a technique from modern wildlife population biology to account for the inherent incompleteness of the fossil record, and it enabled them to get an idea of the size and structure of the population at large during the period in question.

Once completed, the researchers could then directly compare the climate data with the fossil record, and they found that the results did not yield a significant correlation between environmental variation and rates of species origination or extinction, suggesting that environmental variability and species turnover may not be closely related.

Detailed detective work

The large study, which is part of the Hominin Sites and Paleolakes Drilling Project (HSPDP) that began 12 years ago, featured a huge amount of data from different sources, and as an expert in sedimentology, microfossils and geochemistry, Professor Owen played a key role in analysing the samples and resulting climate data.

In total, Professor Owen and the other researchers analysed samples taken from lakebeds, ocean floors and terrestrial outcrops from 17 locations throughout the African continent and surrounding areas. This also included drilled core samples that Professor Owen and Dr Veronica Muiruri, a former HKBU PhD student, had collected from East Africa that looked at the record of diatoms – a type of single-celled algae – in lake cores, as well as pollen data and major and trace elements.

“One unique part of the study is that we have put together the data our group collected from five sites in East Africa and combined this with data from other parts of Africa, and also the seas around Africa, and then we have tried to work out just how much variability in the environment there was,” he says. “Essentially, we have a five million year-long record, and while we couldn’t use all of it for statistical reasons, if the variability selection hypothesis was true we would expect that when things become more variable there should be more speciation and extinction. What we found was that overall the data says that there is no link.”

Comparing the data

But with all this data came a problem, as to explore the relationship between variations in the climate and evolution, the research team needed to first find a way to combine climate data from very different types of records, including pollen, algae, dust, and soil. As a result, to evaluate the wide array of climate data, the researchers devised some clever statistical methods that allowed them to quantify variability and compare it from one sampling location to another, and it required some painstaking work.

“It’s a bit like being a detective,” says Professor Owen of the analysis of the drilled core samples, “so you look at the core for different clues. And you get a clue about a particular environmental change, and then you try and explain that change. Essentially you are looking to see whether anything significant happens simultaneously in the different samples from various locations.”

To make the different samples more comparable, the researchers also assigned the numerous bits of climate data to “bins” of time comprising 20,000, 100,000 and 400,000 years. This enabled the team to standardise the collected data, and they could then calculate the average amount of climate variability in each time period. Once the climate data had been standardised, the team were then in a position to compare it with the fossil record to see if changes in the climate matched up with periods of evolutionary change.

“There are so many different sets of data that you can’t just add them together, but by translating them into comparable units and looking at the relative variability, you can then pull all the data together,” says Professor Owen.

Hopefully our discoveries will change the way scientists view the relationship between climate change and the fossil record in Africa, and especially the human fossil record.

Professor Bernhart Owen

Department of Geography

Shifting the scientific consensus

Overall, the landmark study provides a detailed picture of the shifts in climate, as well as changes in the fossil record, over the past four million years. If, as the longstanding variability selection hypothesis suggests, shifting conditions led to our ancestors becoming more resourceful, which in turn, led to new species appearing while others went extinct, the team would have seen this in the data. But instead, they found no link.

Yet while the current study has cast doubt on the variability selection hypothesis over long periods of time, the authors do acknowledge that the hypothesis could still be correct but operating at different scales. As a result, they hope to encourage the scientific community to think about the hypothesis in a more critical way, rather than just accepting it as an underlying principle of how we look at the fossil record in Africa.

“Hopefully our discoveries will change the way scientists view the relationship between climate change and the fossil record in Africa, and especially the human fossil record,” adds Professor Owen.

Previous News

Next News